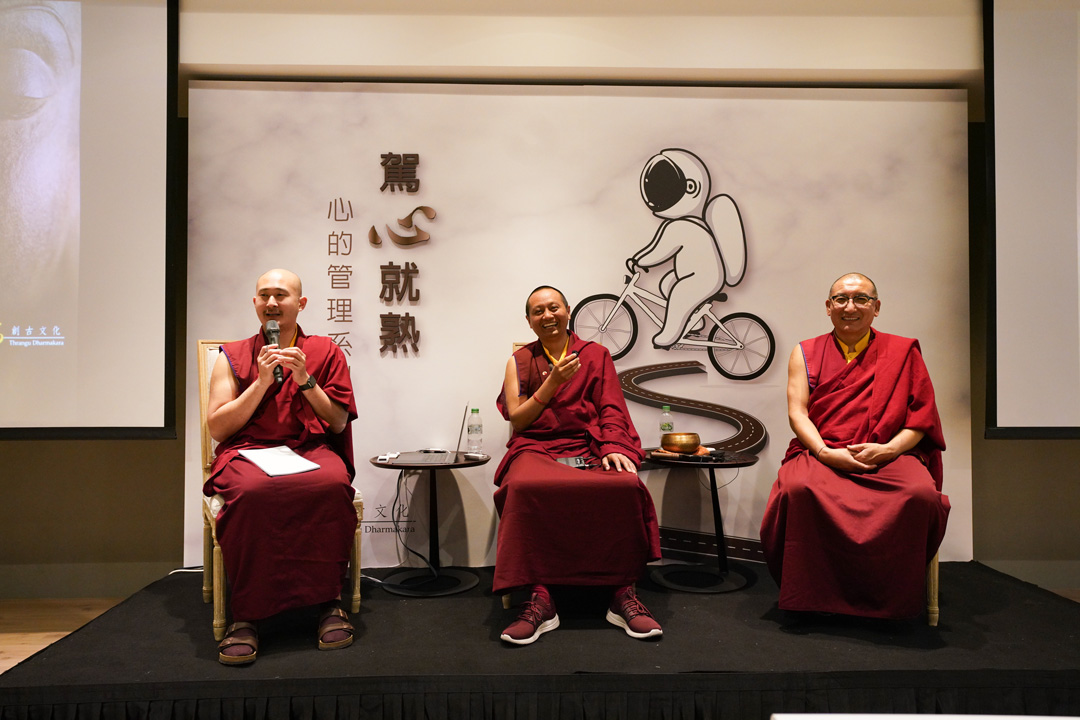

【COLUMN∣JAMYANG 】Mind Management Teachings:(六)Khenpos swear too? Five questions about Mind Management

Students seized the opportunity to ask all three Khenpos various practical questions and their advice on managing the mind in daily lives. By bringing the discussion from the classroom to the field, students become better equipped to build a grounded practice in their daily lives.

Q1: Do you cuss or use swear words?

Khenpo Chonyi:

I became a monk at 7, and I’ve always been the one with the worst temper at the monastery. But reading Shantideva’s The Way of the Bodhisattva changed me. I studied, contemplated, and meditated continuously on this text for two years, and it has tamed my mind. Now, I swear sometimes in a joking manner, but never when I’m actually angry.

Khenpo Dawa

I’ve worked in Hong Kong for many years, and when I’m managing large events or dealing with a lot of administrative work, there are occasions where I have to scold or criticize people, but I will check whether my motivation is from a wish to benefit myself and others.

As for swearing, I think it’s related to one’s personality. Sometimes, I get so angry that I find myself with a non-virtuous intention, but I still don’t resort to swearing as a way to express myself.

Khenpo Tengye:

I look like a person easy to get along with, but I feel that I have quite a bit of anger in me. I tend to bottle them up gradually until I eventually explode. I don’t have a habit of swearing due to my upbringing, but I find using alternative expressions which go unnoticed are just as satisfying. (Everyone laughs)

Anger cannot be forcibly suppressed when we are dealing with emotions; it arises naturally under certain conditions, but it only exists in that specific moment. Studies overseas have shown that if a frustrated person can vent their emotions through yelling, they are able to withstand suffering longer than those who try to suppress it.

Q2: How to discern between ordinary anger and compassionate anger?

Khenpo Chonyi:

Actually, we are incapable of deceiving ourselves, since we can clearly notice if our motivations are virtuous or not. To gain insight into someone else’s motivation, first, we have to listen calmly, really feel what they are saying, and then observe with wisdom. If we fail to do so and react rashly out of ignorance, we bring in more emotions and further complicates the situation.

If someone gets angry with me, I won’t react right away. I will wait till the next day, the day after, or even longer to make sure he actually meant what he said. I have to determine if his motivation and behavior are in tune or not. The next time we meet, if he seems to be still vengeful and overcome with hatred, it shows that the anger he expressed was based on afflictions. However, if he is still supportive and caring towards me, worried if I felt uncomfortable from our previous interaction, this indicates that he genuinely has my best intentions in mind; the anger he previously displayed came from a place of compassion.

By facing people pretending to be virtuous, we can better assess where our practice is at. The best practitioners give rise to compassion, seeing that the other person is unknowingly under the control of afflictions. They employ skillful means to resolve the situation. Under general circumstances, we can also choose to maintain our distance from them. If we can’t provide help, at least we can avoid conflict and prevent ourselves from being affected by them.

Q3: How can we maintain our concentration?

Khenpo Chonyi:

Our present environment makes us distracted very easily, and many of current society’s problems stem from being distracted. To remain undistracted in a complicated environment, we need to have mindfulness and awareness. From a worldly perspective, if we have three tasks to accomplish today, we have to remind ourselves to focus on them using mindfulness. As long as we have awareness, which is a state of knowing, we can return to the task at hand even if we become occasionally distracted. Through “pulling” ourselves back repeatedly, we can be free from distractions and maintain mindful concentration.

Q4: Why do we still want to eat even though we are already full?

Khenpo Dawa:

The mind is in charge of speech and body. If it is afflicted by desire and attachment, we lose control of our bodies and start craving food. In other words, we need to work on our minds to remove this affliction.

Khenpo Chonyi:

This is related to the five sensory desires which Buddhism talks about: forms, sounds, smells, tastes, and touch. For a practitioner, we don’t aim to avoid these pleasures but to fully experience them. When we eat, not only are we attracted to the smells, but factors like color and presentation all play a part in stimulating our appetites. When we clink our glasses together, savor the variety of tastes in our mouths, feel satiated once the food settles in our stomachs, we experience the sensory desires once again.

The best experience is to have a balance between all the sensory pleasures, without overindulging or being obsessive in one. If we still crave food even though we’re full, it shows that we’ve been eating without satisfying our sense of taste. We need to be aware of our sensory desires and maintain a balance between them.

Q5: How can we settle down and practice Dharma while being busy with work?

Khenpo Dawa:

Actually, we can benefit others while working, but we have to be careful of our self-grasping mind. Even if we are doing virtuous activities, we cannot truly benefit others like the Buddhas have if we are plagued by an inflated ego.

Since I am in charge of Dharmakara in Hong Kong, I am busy with numerous projects and events. The busier it gets, it becomes more important to find opportunities to practice.

When we wake up in the morning, we can give rise to Bodhicitta to remind ourselves to help others while at work. Even if we are unable to help, or if the other person refuses, we should still remind ourselves of the motivation to benefit others. If we have a virtuous intention behind everything we do, it makes our work go smoothly and more effectively. We won’t become hurt or devastated even if we fail at our tasks occasionally, because our altruistic intentions instantly motivate us to search for other ways to help others.

Khenpo Chonyi:

We tend to become distracted and lose our peace of mind when we become busy. The easiest method to practice in our daily lives is to recite mantras. We can recite Chenrezig’s six-syllable mantra, which represents the essence of compassion and wisdom. Many teachers make their students recite the mantra a million times in the beginning.

Reciting mantras is a personal practice that others don’t have to know about. By reciting quietly in our spare time, we can arouse a virtuous mind with Chenrezig’s blessings. Choosing to recite mantras in our free time helps us to concentrate, so we will naturally refrain from activities like meaningless gossip or swiping around our phones. We become more confident once we accumulate a million recitations, which signifies our ability to practice continuously.

▸Related◂

- (一)Understanding the mind and taming our afflictions: First of the Mind Management series in Taipei

- (二)Khenpo Tengye:Recognize your mind

- (三)Khenpo Dawa:Manage the mind and be your own master

- (四)Khenpo Chonyi:Learning about the mind: First, forget who we are

- (五)Let’s talk about our minds today

- (六)Khenpos swear too? Five questions about Mind Management

JAMYANG 蔣揚

A native of Taiwan, Jamyang grew up in Singapore and gradually developed an interest in studying languages. He is currently learning Tibetan.

出生在台灣的蔣揚,在新加坡長大,並對語文感到興趣,目前正在學習藏文。